A bar in Burlington, Vermont, an October afternoon—a beery atmosphere, a slight cigarette smoke haze to the proceedings. There’s a television to the left of the bar affixed to wall, tuned in—as is the case whenever possible—to sports, in this case, a one-game playoff between the New York Yankees & the Boston Red Sox to determine which team will win the American League Eastern Division for the 1978 season.

A bar in Burlington, Vermont, an October afternoon—a beery atmosphere, a slight cigarette smoke haze to the proceedings. There’s a television to the left of the bar affixed to wall, tuned in—as is the case whenever possible—to sports, in this case, a one-game playoff between the New York Yankees & the Boston Red Sox to determine which team will win the American League Eastern Division for the 1978 season. The crowd in the bar is divided in its loyalties—this is western Vermont, a no-man’s land in the long-standing northeastern feud between the two teams; local cable TV broadcasts both a station that carries Yankees games & one that broadcasts the Sox (as well as Canadian Broadcasting, which airs a mix of Montreal Expos & Toronto Blue Jays—in those days before the proliferation of available games on cable & satellite, this was a true bonanza.) I don’t recall which station was on that day, but I was in that bar with three friends: two Yankees fans & one Red Sox fan; & my loyalty ran very much toward Boston.

Last week when I wrote about memory & desire in baseball, I focused on the romanticism of finding the artistry of past players reincarnated in present players—an aesthetic appreciation, a positive articulation of memory. But baseball contains so much other memory—it’s a game that’s fraught with failure & disappointment. The old adage points out that the best hitters will fail to get a base hit about 70% of the time, & while some of the outs recorded in that 70% will actually produce positive results, even if one counts all the positives, the greatest hitters fail well over half the time. While the percentage of failures are lower for pitchers, all of them have bad games at least occasionally.

& baseball is uniquely a game of individual failure (or success.) The batter is a solitary figure at the plate, the pitcher a solitary figure on the mound. We focus on them. The experienced fan, if he/she is at the park, may also watch the movements of the fielders or any base runners, but by & large the focus is on this one-on-one confrontation—certainly that’s how the TV cameras are directed.

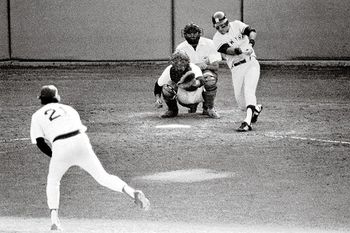

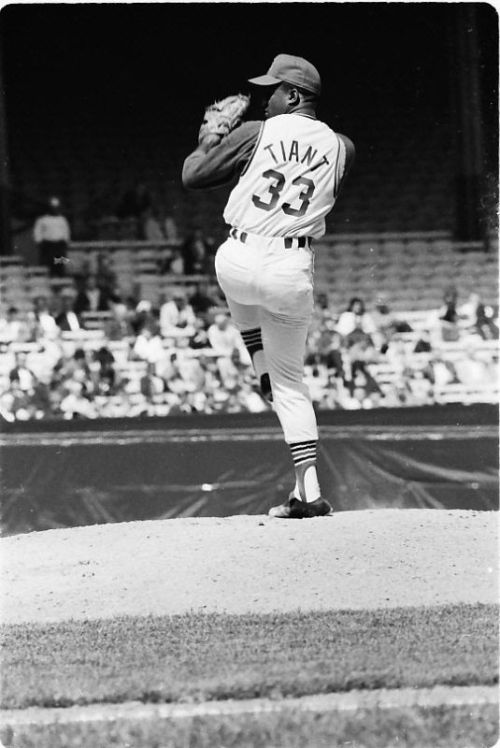

The Red Sox lead 3-0 in the top of the 7th inning—but the Yankees have two base runners on with 2 outs. The batter is the Yankees’ 9th place hitter, Bucky Dent, a light-hitting shortstop who’s hitting .243 for the year with only 4 home runs; in fact, Dent has been in a slump, hitting a mere .190 over the past 20 games. The Red Sox starting pitcher, Mike Torrez is on the mound. He has the second most wins on the team, 16 behind Dennis Eckersley’s 20-win campaign. On the other hand, he’s given up more hits than the number of innings he’s pitched, & he’s walked almost 100 batters. But on the plus side, he’s given up the fewest home runs of any Red Sox starting pitcher—just 19, despite playing in a park that’s notorious for yielding home runs.

Of course, that shouldn’t be a consideration in this case. Dent is not a home run threat, & he also fouls Torrez’ second pitch off his foot, causing an injury delay while he walks off the pain. Apparently during this time, the on deck hitter, Mickey Rivers, noticed that Dent’s bat was cracked, & so loaned Dent his bat. Dent returned to the batter’s box & promptly served Torrez’ next pitch into the netting atop the left field wall for a 3-run home run. The Yankees took a 3-2 lead & held on to win the game 5-4, with their fearsome reliever Goose Gossage inducing Red Sox Hall-of_fame left fielder Carl Yastrzemski to hit a pop fly out to third with 2 on base & 2 out in the bottom of the 9th inning.

The fact that in most major league ballparks, which have much less cozy left field dimensions than Boston’s Fenway Park, Dent’s ball would likely have been caught for the third out only rubs salt into the wound—the Red Sox lived by the “Green Monster,” as it yielded home runs & doubles for their team—& in this case, died by it.

Over the course of many years of watching baseball, I’ve experienced other disappointments as a fan as keen as I experienced that afternoon; & now I don’t recall if the beer made the disappointment more sour or not—I expect it probably did. There was the evening in 1986 in a rental house in Albemarle County, Virginia when I witnessed Bob Stanley & Bill Buckner’s 10th inning meltdown for the Red Sox costing them what would have been the deciding game of the World Series against the Mets; there was the evening in an Idaho farmhouse, October 2002, when I saw Giants manager Dusty Baker pull starting pitcher Russ Ortiz after 6-1/3 innings in another game 6, Giants leading 5-0 with a lead of 3 games to 2 in the best of seven series, only to see the Anahiem Angels erupt for 6 runs in the next two innings against a Giants relief pitching staff that had been masterful all year.

Those are the most egregious examples, but on any given day, the fan experiences disappointments & chagrin as the vicissitudes of the game alternate between success & failure. Of course, in my own small way, I found this to be true when playing the game as well—the difficulty to remain confident & unjangled following a bad play in the field or a bad at bat. This is something I was never good at in the least, & I believe it encapsulates why I played better in the pick-up games where much less was “on the line” (at least in my imagination) than when my friends & I fielded the Mission team in the Roberto Clemente league.

Because, after all, these vicissitudes of success & failure are imaginary as the game is itself—an imaginary game with a hardball & spikes & hardwood bats & leather gloves; an imaginary game in which it’s impossible—on one side of the ball—to succeed even half the time, & on the other side of the ball to have your failures magnified by the cost to your team.

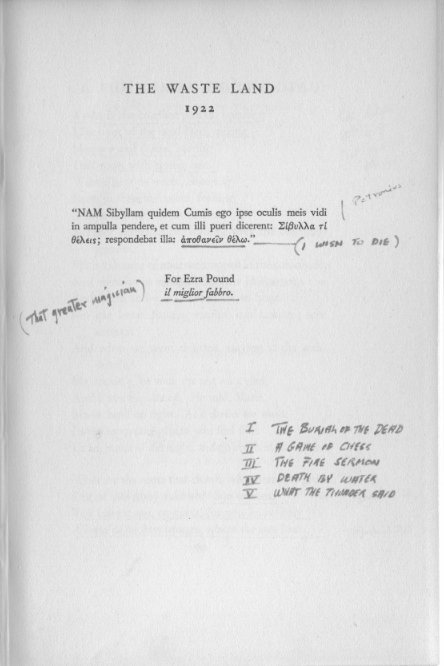

The moral of the story: the “point” towards which this ambling, digressive post has tended—is that as a fan experiencing baseball, the possibility of experiencing memories of failure—not just failures in past games, but failures in life far removed from the imaginary narrative of a sport—is pungent; the game can truly take you to a Wasteland of the spirit; you become the Sybil of Cumae telling the boys “I want to die.” There is talk of curses, a sense that the universe has some stake in your failure & that of your beloved team. This is a dark side of the memory & desire quotient, & a side that makes the desire all the more desperate: that the team will win against all the odds of failure, & you as fan will somehow—again imaginatively—be justified in that winning.

Since 2002, I’ve found myself as a fan becoming more dispassionate, more of an observer. I can’t say this is altogether a positive turn of events, but perhaps it’s a necessary one. In my late middle age, I no longer gravitate toward the strong passions of my youth. But I was elated when the Red Sox improbably finally won their first World Series in 2004 & again in 2010 when an underdog San Francisco Giants team took its first Series since 1954.

But I’m happy—I believe—to say that I was not justified; I didn't feel any personal curses lifted. Because I’ve always questioned the “truth” of Eliot's final lines of “The Wasteland.”

All pix link to their source

top pic: The epigraph to "The Wasteland"

pic 2: Dent's Home run swing

pic 3: the "Green Monster"

pic 4: Red Sox first baseman Bill Buckner boots Mookie Wilson's grounder in Game 6, 1986 Wold Series, allowing the winning run to score for the Mets

pic 5: Meeting on the mound for the Giants as Dusty Baker relieves Russ Ortiz in Game 6 of the '02 Series

pic 6: the Bambino-Babe Ruth-as a Red Sox pitcher. The sale of Ruth by Red Sox owner Harry Frazee in 1920 to the Yankees-as a way of raising money to finance his production of "No, No Nanette"-was he source of the so-called "Curse of the Bambino" that supposedly kept the Red Sox from winning a World Series from 1918-2003.Pic 7: Red Sox relief pitcher Keith Foulke & first baseman Doug Mientkiewicz engage in levitation & jubilation following the final out of Boston's decisive win in the 2004 World Series