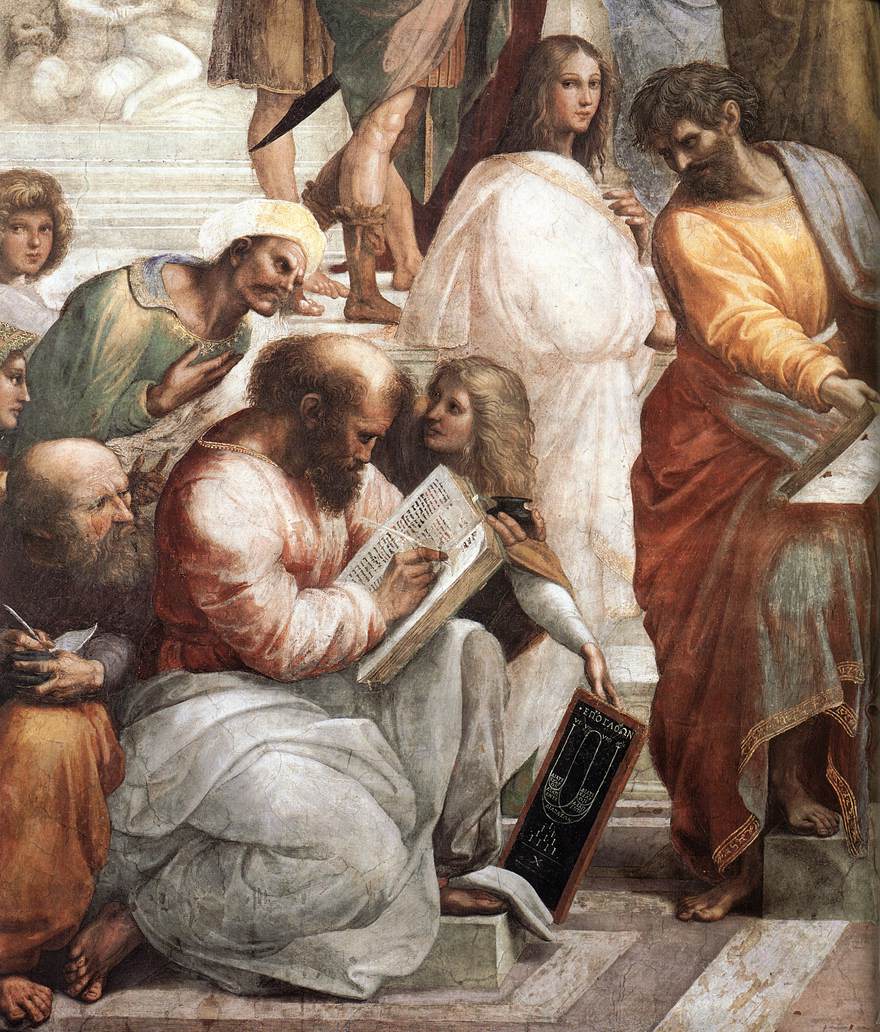

Now, as I’ve suggested in other posts, there is a stance toward baseball numbers that is indeed Platonic in its underlying assumptions (tho with more than a touch of neo-Platonism, with the frankly mystical idea that a major function of statistics is to be predictive even more than descriptive); it isn’t difficult to see that a certain insistence on figures like Pythagorean Wins or BABIP or xFIP becomes an appeal to a realm beyond that of perceived reality. In such a reading, the Baltimore Orioles of 2012 aren’t really a good team, despite the fact that they have the second most wins in the American League; the Arizona Diamondbacks catcher Miguel Montero isn’t really a .293 hitter, because his BABIP (batting average on balls in play) is an unsustainable .368; Jered Weaver of the Los Angeles Angels may not really be the dominant pitcher he appears to be at first glance, as his xFIP (Expected Fielding Independent Pitching) is a pedestrian 4.10. Thus, we have the Baltimore Orioles, Miguel Montero & Jered Weaver who exist in the material world of change, but we also have the “form” of all three entities (as it were) in the immutable world of forms.

In European cosmology, this drive for immutability may have been conceived most elegantly in the Aristotlean/Ptolemaic model of the cosmos, in which the earth is at the center of the universe, & is ringed by eight planetary spheres: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, & the region of Fixed Stars. Mutability ruled in the sublunary world (the Moon being the changeable heavenly body)—John Donne, in his "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” refers to “dull sublunary lovers’ love—whose soul is sense”—that is, lovers who are trapped in the material & transitory world below the moon; & even in the 20th century, W.B. Yeats wrote (in “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen”):

Many ingenious lovely things are gone

That seemed sheer miracle to the multitude,

Protected from the circle of the moon

That pitches common things about.

In the Ptolomeic cosmology, there could be no change in the region of fixed stars—which explains the absolute disruption to this model when astronomer Tycho Brahe determined that the 1572 supernova in the constellation Cassiopeia was in fact a new star, “never before seen in the life or memory of anyone” (a translation of the title of his treatise, De nova et nullius aevi memoria prius visa stella.) Thus, Brahe showed, the “Region of Fixed Stars” wasn’t actually fixed & immutable at all—stars appeared & vanished (Brahe also demonstrated that comets, rather than being sublunary events, passed thru the supposedly immutable sphere.) The importance to western cosmology & philosophy of Brahe’s supernova, or SN1572 as it is designated, can hardly be under-estimated.

But now we move to the realm of baseball, where Platonism—as it does perhaps in the popular culture overall—still exerts a powerful force! Within the universe of baseball—the game of numbers—there are certain statistical figures that have an immutable quality, & if they admit some change over the course of time (because, like any good western sacred drama, baseball exists simultaneously in historical & mythical time), there meaning remains unchanged. Among these figures the meaning of which has remained apparently immutable, we would name the “great” career statistics of 300 wins for pitchers & 3,000 hits & 500 home runs for hitters. Certainly throughout the lifetimes of most baseball fans, the meaning of those three numbers has seemed immutable—once a player attained to any of those numbers, his greatness is a fait accompli; he becomes a fixed quantity—in baseball terms, a Hall of Famer.

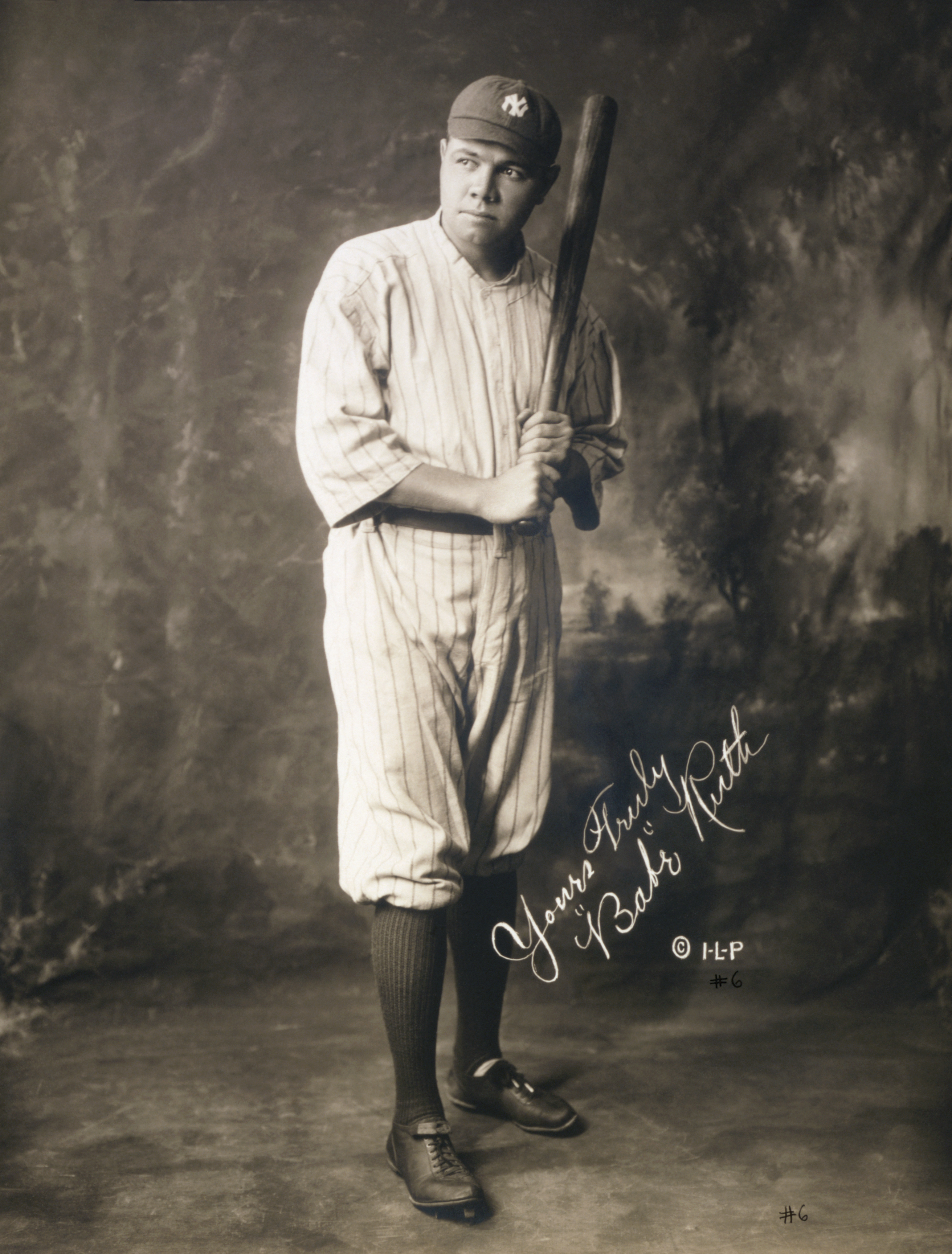

All three of these numbers are worth examining in hermeneutic terms, but for today, let’s simply consider 500 home runs, & let’s look back 50 years to 1962. In that year—within my lifetime, tho a few years before my interest in baseball became keen—there were only four men who’d achieved 400 home runs in their career: Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Ted Williams, & Mel Ott. The meaning of 500 home runs was that these four players were the greatest of the great in terms of power hitting, & Ruth, who’d shot well past the 500 region of fixed stars into the empyrean of 714 home runs had indeed transcended the game; a legend, even a myth within 20th century U.S. culture. Meanwhile, the remainder of the top ten were also the greatest of the great, even Gil Hodges in 10th place with his 370 lifetime home runs. Stan Musial, Mickey Mantle & Eddie Matthews, the three active players on the list (Williams had retired at the end of the ’61 season) were all destined for legendary status themselves.

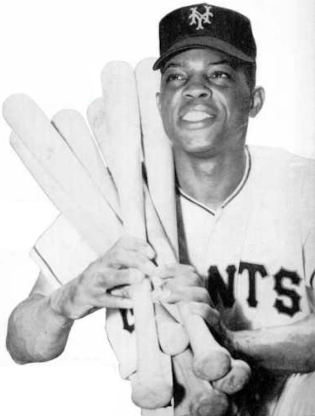

But if we skip ahead a mere 10 years to 1972, we see that this unalterable top 10 list is much changed. To begin with, 500 home runs has now become the essence of greatness: none of the best of the best have hit fewer than 512 home runs, & in fact Mel Ott, the great Giant, has slipped out of the “region of fixed stars,” while newcomers Ernie Banks, Frank Robinson, Harmon Killebrew, Willie Mays & Hank Aaron have entered the realm of immutable greatness—in fact, Aaron & Mays have both surpassed the 600 home run barrier & stand on a threshold to Ruth’s 714 empyrean. In fact, eight of the ten members of this group had playing careers that included at least some of the 1960s.

By 1982, the list had grown to 11, simply because Ernie Banks & Eddie Matthews remained tied for the final spot with 512, while Willie McCovey had also joined the group. Actually, this configuration obtained from 1979 thru 1984 (the only change being that McCovey hit one more home run to tie Ted Williams at 521); & I’d say it was this grouping that dates from around 1972 that has been formulated in more recent memory into the concept that 500 home runs is a numerical form that is the essence of a Hall of Fame slugger. Certainly that wasn’t the case when the Hall of Fame accepted its first inductees for enshrinement in 1936; at the end of the 1936 season, only Ruth had surpassed 500 home runs (he already had his 714, having retired in 1935.) Lou Gehrig was the only other major league player who had surpassed 400 home runs at that time.

By 1982, the list had grown to 11, simply because Ernie Banks & Eddie Matthews remained tied for the final spot with 512, while Willie McCovey had also joined the group. Actually, this configuration obtained from 1979 thru 1984 (the only change being that McCovey hit one more home run to tie Ted Williams at 521); & I’d say it was this grouping that dates from around 1972 that has been formulated in more recent memory into the concept that 500 home runs is a numerical form that is the essence of a Hall of Fame slugger. Certainly that wasn’t the case when the Hall of Fame accepted its first inductees for enshrinement in 1936; at the end of the 1936 season, only Ruth had surpassed 500 home runs (he already had his 714, having retired in 1935.) Lou Gehrig was the only other major league player who had surpassed 400 home runs at that time. & indeed, Ruth was the only inductee in 1936 who had amassed what we’d consider a remarkable number of home runs; the two other position players named were Ty Cobb (who got the highest percentage of votes & had 117 career home runs) & Honus Wagner (101 home runs—which as late as 1922 had him in a tie for 10th place all-time!) The next player inducted who’d be considered a slugger by today’s standards was Lou Gehrig in 1939 (with his 493 home runs in a career cut short by the terrible disease that has been given his name); following Gehrig, the next that would even come close to being a slugger by today’s definitions would be Rogers Hornsby in 1942 (301 career home runs, which kept him in the top 10 thru 1952); & then finally the next two 500 home run hitters, Jimmie Foxx & Mel Ott in 1951.

But recently, 500 home runs has come to be seen differently: the region of fixed stars is no longer immutable (not, as we see now, that it ever really was!) As of this writing, only four of the eleven men found on the 500 home run list in the defining post 1972 period are still among these greatest of the great: Ruth, Aaron, Mays & Frank Robinson.

Just as Brahe observed that changes occurred in the so-called region of fixed stars, we observe that changes have occurred to 500 home runs—whereas there were three such players 50 years ago, there are now 25 (& soon 26, as Albert Pujols is only another good season away from the total): a 1150% increase. We don’t seem to accept that there can be 25 players among the unquestionably great—three, yes; a dozen, yes. Even when the list expanded to include Mike Schmidt & Reggie Jackson in the 1980s, consensus didn’t waver. But when Rafael Palmeiro ended his career with 569 home runs & Gary Sheffield retired with 509, there was a growing contrary consensus that 500 was no longer the immutable figure we had thought. In addition, when the names of several of the players who have achieved 500 home runs (& in some cases, 600 or 700) within the past decade were also linked to rampant use of performance-enhancing drugs, then the supernova had exploded. What did it mean that Barry Bonds hit more home runs than any player in major league history (762) when there is a large amount of circumstantial evidence pointing to his use of such substances? What does it mean that Alex Rodriguez has hit 647 to date or that Mark McGwire hit 583, when they admitted themselves to the use of these drugs; what does Palmeiro’s total mean in the light of a failed drug test?

These are interesting questions, of course, tho ones to which we won’t ever really have answers. More to the point in my mind is the fact that, just as there never was an immutable region of fixed stars, the “immutable” meaning of 500 home runs has simply been a historical phenomenon that at most had significance for approximately 50 years of major league baseball’s 136 year history. For that matter, 100 home runs was a very significant figure for about the same amount of time; Harry Stovey became the first player to 100 in 1890, & as recently as 1931 half of the top ten home run hitters of all-time had totals between 169 & 196; 1934 was the first year when a total of 200 was required to make the top ten.

The mutability of meaning & being: even in baseball!

All images link to their source

- Babe Ruth, 1920: Wiki Commons - public domain (Library of Congress)

- The Ptolomeic Cosmos (1524 print): Wiki Commons - public domain

- Tycho Brahe's star map of the constellation Cassiopeia showing the position of the Supernova of 1572 (the supernova is the large star marked "I"): Wiki Commons - public domain

- Mel Ott, 1940 Bowman Gum baseball card: Wiki Commons - public domain (copyright expired, not renewed)

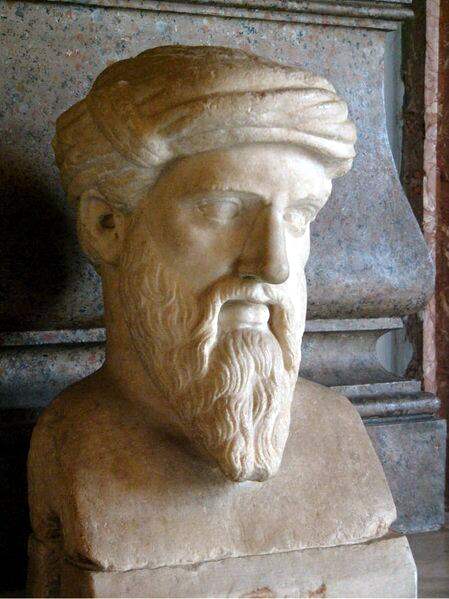

- Tycho Brahe: Wiki Commons - public domain

- Mark McGwire: "Mark McGwire, St. Louis, 2001. This picture was taken during a Saturday afternoon game against Detroit on July 14, 2001. It depicts McGwire's 10th home run of the season and 564th of his career, moving him ahead of Reggie Jackson for sixth on the all-time list." Wiki Commons - by Rick Dikeman, who publishes it under the under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

- Harry Stovey on a 1887-1890 Goodwin & Company baseball card (Old Judge (N172)): Wiki Commons - public domain

- Composite X-ray and infrared image of the SN 1572 remnant as seen by Chandra X-Ray Observatory, Spitzer Space Telescope, and Calar Alto Observatory: Wiki Commons/NASA - public domain

.jpg)

_(5966121708).jpg)

.jpg)