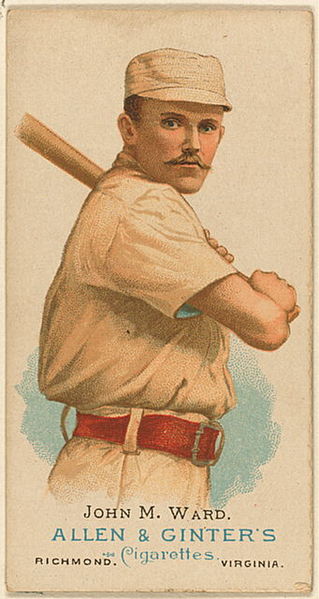

When I was young I had a strange fascination with the baseball career of a player named Richie Scheinblum. At the time he was playing right field for the Cleveland Indians, tho later in his career he played for the Washington Senators, the Kansas City Royals, the Cincinnati Reds, the California Angels, & the St Louis Cardinals—an 8-year career, counting his brief stay with the Indians in 1964, with the 8 major league seasons occurring over the span of 10 years. During that career his “triple slash line” of .263/.343/.352 for a .695 ops.

Now that’s a lot of numbers for the readers here who aren’t baseball aficionados, so in brief: his batting average was just “ok” (he played during a time when pitching was dominant); despite that, he got on base quite a lot (taking walks), but his power was lacking, especially for a corner outfielder. Richie Scheinblum was, taken all in all, at best an average major league ballplayer.

But put Richie Scheinblum back in the minor leagues & watch out! In 1970 in Wichita his line was .337/.424/.576 for a 1.000 ops, & the next year in Denver he put up the following mind-boggling hitting stats: .388/.490/.725, 1.215 ops. People will rush to say that he was old at the time for the minors (true) & that the Denver stats were inflated (so to speak) by the altitude (also true), but as a teenager in the early 1970s, who paid attention to that?—what you knew was what was on the back of the bubble gum card (which, of course at that time only gave a player’s batting average & “counting stats” like home runs, runs batted in & so forth.)

Nonetheless, from relatively early in my baseball fandom I had a concept of the so-called “4-A” or in the current parlance “Quad-A” player—the player who could dominate the highest level of the minor leagues (Triple A), but whose dominance there doesn’t carry over into the major leagues. This concept has been applied to a number of players over the years, fairly or unfairly. There’s a notion nowadays that the “4-A” player is essentially a myth, & that either his minor league statistics were misleading (see my note on Scheinblum) or his development was mishandled by his team.

Nonetheless, from relatively early in my baseball fandom I had a concept of the so-called “4-A” or in the current parlance “Quad-A” player—the player who could dominate the highest level of the minor leagues (Triple A), but whose dominance there doesn’t carry over into the major leagues. This concept has been applied to a number of players over the years, fairly or unfairly. There’s a notion nowadays that the “4-A” player is essentially a myth, & that either his minor league statistics were misleading (see my note on Scheinblum) or his development was mishandled by his team.Of course, minor league players—“prospects”—have come much more to the forefront of fans’ consciousness over the past 25 years or so. Somewhat hand-in-hand with the fantasy baseball industry, there are now (& have been for some time) numerous publications & websites (many of these being pay subscription-based either entirely or in part) devoted to minute analysis of young players potentially on their way to the major leagues.

There are many narratives, but in general, the frog is always a prince before the kiss—otherwise, there would be no kiss. The sleeping beauty & the prince charming are always already destined for happiness before the waking; prospects are indeed the fairy tale happily ever after of professional baseball. & unlike the frog or the sleeping beauty or the prince charming, there even seems to be evidence of their happily ever after potential: look at what he did in Fresno or Wheeling or Pawtucket—he will be a dominant hitter or pitcher, there’s no question, & he will be integral to bringing the team to a championship happy ending. The fan tells himself/herself this narrative again & again: this is not a knock on the fan; this is what fans do—this sort of narrative is part of the very definition of fanhood.

But the story doesn’t always go like that—in fact, given the number of prospective players who are inhabiting these narratives at any given point, only a statistical minority even become average major league players, let alone the Frog Prince. But there’s a more interesting question perhaps: when does one recognize that the Frog Prince was actually a frog after all? When does it become clear that the marriage of Prince Charming & Sleeping Beauty is not the ideal match we all imagined, but at best a typical marriage with ups & downs; at worst, a romantic match made in hell. This reminds me of the great fantasy novel, The King of Elfland’s Daughter by the redoubtable British peer Lord Dunsany—to my mind one of the best novels in that genre. Dunsany tells the story of how Alveric, the Prince of Erl, travels to Elfland & brings back Lirazel, the transcendently beautiful daughter of the king, to be his bride in the mortal lands. Thru the first several chapters we have the usual happily ever after fairy tale: but then the tale turns grim: heartbreak, alienation, the power dynamics of marriage, exile; tho fantasy, we learn something real about “romance.” But the baseball fan is always a romantic….

But the story doesn’t always go like that—in fact, given the number of prospective players who are inhabiting these narratives at any given point, only a statistical minority even become average major league players, let alone the Frog Prince. But there’s a more interesting question perhaps: when does one recognize that the Frog Prince was actually a frog after all? When does it become clear that the marriage of Prince Charming & Sleeping Beauty is not the ideal match we all imagined, but at best a typical marriage with ups & downs; at worst, a romantic match made in hell. This reminds me of the great fantasy novel, The King of Elfland’s Daughter by the redoubtable British peer Lord Dunsany—to my mind one of the best novels in that genre. Dunsany tells the story of how Alveric, the Prince of Erl, travels to Elfland & brings back Lirazel, the transcendently beautiful daughter of the king, to be his bride in the mortal lands. Thru the first several chapters we have the usual happily ever after fairy tale: but then the tale turns grim: heartbreak, alienation, the power dynamics of marriage, exile; tho fantasy, we learn something real about “romance.” But the baseball fan is always a romantic….Which brings us to current Giants first baseman, Brandon Belt, the “Baby Giraffe.” As the

nickname suggests, Belt is a gawky young man (& there has been some criticism of him based on what he calls his awkwardness that, in my opinion, is unwarranted)—but look at his minor league stats! At three minor league levels in 2010, he put up a .352/.455/.620/1.075 line, & in two levels in 2011 he was only slightly less dominant at .320/461/.528/.989. Last year in 63 games with the Giants his stats were underwhelming: .225/.306/.412/.718, but he was only 23 & 63 games is a small sample; in addition, his playing time was inconsistent—something that has driven certain San Francisco Giants fans to distraction. Their watchword is “Free Brandon Belt!”—i.e., provide him with consistent playing time, don’t bench him after a poor game, try to put him in positions to succeed.

nickname suggests, Belt is a gawky young man (& there has been some criticism of him based on what he calls his awkwardness that, in my opinion, is unwarranted)—but look at his minor league stats! At three minor league levels in 2010, he put up a .352/.455/.620/1.075 line, & in two levels in 2011 he was only slightly less dominant at .320/461/.528/.989. Last year in 63 games with the Giants his stats were underwhelming: .225/.306/.412/.718, but he was only 23 & 63 games is a small sample; in addition, his playing time was inconsistent—something that has driven certain San Francisco Giants fans to distraction. Their watchword is “Free Brandon Belt!”—i.e., provide him with consistent playing time, don’t bench him after a poor game, try to put him in positions to succeed.This year so far, Belt has also produced mostly pedestrian numbers—.238/.344/.379—but look at the middle number: a .344 on-base percentage is quite good, & if you look back at his minor league numbers, you’ll notice that this has always been a strong part of his game. High on-base percentage is highly valued, especially amongst the sabermetric folks, & with good reason: to score runs, you have to be on base.

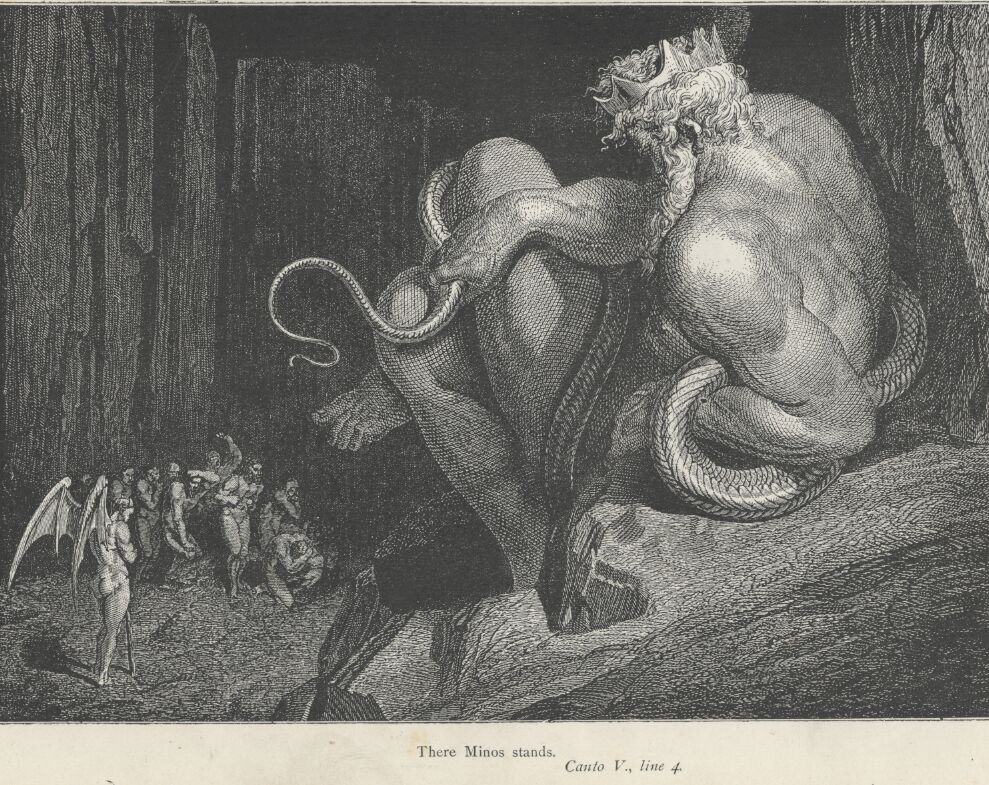

There are more characters in the Belt fairy tale, of course, most notably the Giants’ field manager Bruce Bochy & to a great extent the Giants’ general manager Brian Sabean. In many of the Belt narratives, Bochy in particular plays the role of “Tyrant Holdfast,” the symbol of the old order who tries to keep the hero from his destiny: the King Minos to the heroic Theseus. Bochy does fit the role rather well: he is an “old school” manager who is not known to place a high store in the more complex statistical analyses favored by the sabermetrics folks & many baseball fans; he has a decided preference for older, veteran players over younger players, even when there is some strong evidence that the younger players may have the potential for significantly better performance.

Of course, “potential” is the frog; the sleeping princess. Will the frog become a prince, the princess wake, if kissed? Bochy’s position seems to be that Belt isn’t productive enough to be a full-time player. Earlier in the year, he platooned at first with Brett Pill, another prospect, tho one who is less highly-regarded; Pill usually played against left-handed pitchers, despite stats indicating that Belt actually hits left-handed pitching well, despite the fact that he bats left-handed. Later, Belt was given the first base job outright when Pill was sent back to the minors, but despite a brief hot streak earlier in the summer, he has not produced in two specific areas which, one assumes, Bochy holds in high regard: batting average & runs batted in. Of course, these are stats that are held in low regard by the sabermetric community—hence, back to the “Free Brandon Belt!” notion.

For instance, although first base is traditionally a power hitting position, why not bat Belt higher in the order, where his on-base skills, his ability to take a walk, would be an advantage? There’s a theory that Bochy actually sees Belt’s propensity for taking walks as a lack of aggressiveness, & since Bochy has generally batted Belt in line-up spots that should be driving the ball to move runners & score them, the walks lose some of their value—after all, runners move more bases as the result of a hit, & especially an extra base-hit. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that the players hitting after Belt generally are not potent offensive performers, so his walks don’t result in runs as much as they would were he batting ahead of more formidable hitters. However, Bochy & Sabean don’t seem inclined to act on this.

What will become of our potential hero? Some think Belt may be traded to another team—his supporters feel that with better handling he might indeed flourish. Alternatively, he could begin to hit more & go on to a glorious career with the Giants. Some folks have compared him to first basemen like John Olerud & Will Clark, both exceptional hitters who excelled both at batting average & on-base percentage, but whose power was, by first baseman standards, moderate. A hitter like that would go a long way toward improving the Giants chances not only for reaching the playoffs, but indeed having a legitimate chance at a championship run.

Or Belt may stick with the Giants & continue more or less on the same trajectory—the story of The King of Elfland’s Daughter, in which the happily ever after becomes all “too real.” After all, this is the final narrative for most prospects. The fact that the beauty woke up, that the frog became a prince, in the end didn’t mean what we thought it would.

I have no way of knowing; as a Giants fan, I hope that Belt will stay with the team & become a very good player; but for me to say that will happen—no, I’m no prognosticator as I’ve said before. But the narrative will continue to fascinate me—& continue to make me remember Richie Scheinblum.

All photos link to their source

1. Brandon Belt: bleacherreport.com

2. Richie Scheinblum: mlblogsroyalshof.files.wordpress.com

3. Marianne Stokes (1855-1927) - "The Frog Prince": Wiki Commons

4. The King of Elfland's Daughter dust jacket: Wiki Commons

5. Brandon Belt: Wiki Commons; image is by Wiki/Flickr user SD Dirk & published under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

6. King Minos in judgment, from Dante's Inferno by Gustave Doré from Wiki Commons

7. La Belle au Bois Dormant by Gustave Doré from Wiki Commons

8. Will "the Thrill" Clark from examiner.com

9. Richie Schienblum from ootpdevelopments.com

What will become of our potential hero? Some think Belt may be traded to another team—his supporters feel that with better handling he might indeed flourish. Alternatively, he could begin to hit more & go on to a glorious career with the Giants. Some folks have compared him to first basemen like John Olerud & Will Clark, both exceptional hitters who excelled both at batting average & on-base percentage, but whose power was, by first baseman standards, moderate. A hitter like that would go a long way toward improving the Giants chances not only for reaching the playoffs, but indeed having a legitimate chance at a championship run.

Or Belt may stick with the Giants & continue more or less on the same trajectory—the story of The King of Elfland’s Daughter, in which the happily ever after becomes all “too real.” After all, this is the final narrative for most prospects. The fact that the beauty woke up, that the frog became a prince, in the end didn’t mean what we thought it would.

I have no way of knowing; as a Giants fan, I hope that Belt will stay with the team & become a very good player; but for me to say that will happen—no, I’m no prognosticator as I’ve said before. But the narrative will continue to fascinate me—& continue to make me remember Richie Scheinblum.

All photos link to their source

1. Brandon Belt: bleacherreport.com

2. Richie Scheinblum: mlblogsroyalshof.files.wordpress.com

3. Marianne Stokes (1855-1927) - "The Frog Prince": Wiki Commons

4. The King of Elfland's Daughter dust jacket: Wiki Commons

5. Brandon Belt: Wiki Commons; image is by Wiki/Flickr user SD Dirk & published under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

6. King Minos in judgment, from Dante's Inferno by Gustave Doré from Wiki Commons

7. La Belle au Bois Dormant by Gustave Doré from Wiki Commons

8. Will "the Thrill" Clark from examiner.com

9. Richie Schienblum from ootpdevelopments.com