Plutarch, The Moralia

We do acknowledge that baseball—like domestic fowl—enables us to ask cosmic questions. If two separate things that have an apparent separate existence are each essential to the other’s existence, how can one thing pre-date the other? That’s the venerable conundrum about the chicken & the egg—a question that not only engaged Plutarch, but also Plato, Aristotle & late Roman philosopher Macrobius, just to name a few.

Now in the case of baseball, you must have a team & you must have a pitcher—& for the purposes of our examination, you must eventually, at the end of each game, have a win. Of course, you’ll have a loss, too, but that’s only important to our discourse by implication—& we discount the notion of a tie, which in theory at least should never occur. So here is our philosophical conundrum: does the team win because the pitcher is good or is the pitcher good because the team is good?

Just as your take on the chicken & egg question will determine your basic views about creation itself (if we believe Plutarch—& it’s worth noting that Plato & Aristotle, as would be expected, had very different answers), your response to our baseball conundrum will say a lot about whether you favor traditional stats or the more contemporary ones—& of course, will by extension say a lot about your perspective on the game itself.

Just as your take on the chicken & egg question will determine your basic views about creation itself (if we believe Plutarch—& it’s worth noting that Plato & Aristotle, as would be expected, had very different answers), your response to our baseball conundrum will say a lot about whether you favor traditional stats or the more contemporary ones—& of course, will by extension say a lot about your perspective on the game itself.Many people, myself included, realized some time ago that the pitcher win statistic had its drawbacks. Clearly, a pitcher on a team that scores a lot of runs is going to have an easier time gaining wins than a pitcher on a team that scores fewer—anyone who’s followed the Giants over the past several years knows this—tho this year the Giant’s offense is a bit more robust. For instance, Giants ace pitchers Matt Cain & Tim Lincecum have never recorded 20 wins in a season—20 wins having been a long-time benchmark of excellence or proficiency, depending on the era. Cain’s high was 14 wins in 2009, while Lincecum’s was 18 in 2008; & this is despite the fact that many of their other statistics have been top-notch during their careers.

Of course, there have been a few noteworthy exceptions to this—pitchers who’ve amassed significant win totals despite playing on a poor team. The most noteworthy, at least in recent memory, was Steve Carlton who won 27 games for the 1972 Philadelphia Phillies—a team that won only 59 games! In addition to being credited with the win in 46% of his team’s victories, Carlton also led the league in earned run average, strikeouts, complete games (30), innings pitched & strikeout to walk ratio.

Conversely, you have pitchers whose win totals were no doubt helped by being on strong teams. Certainly if you look back at some of the legendary Yankees pitchers like Lefty Gomez & Whitey Ford, you’ll find that they achieved high win totals in seasons that were good, but not otherwise statistically dominant. For instance, Gomez never registered a strikeout to walk ratio greater than 2.09 (this means he struck out just over 2 batters for every one he walked); this was in 1937, & he never reached a 2 to 1 ratio again. In fact in 1936, his K/Walk ratio was 0.86. In Whitey Ford’s famous 25 win season in 1961, his ERA was 3.21—not bad, certainly, but not dominant; likewise, his ERA + was 115, which is only a bit above average, & he also walked 92 batters, which is a high total. Of course Gomez & Ford are both justifiably renowned—but for instance in 1937, when Gomez posted a 21-11 record, the Yankees were averaging 6.2 runs per game; in 1961 while Ford was compiling his 25 win season, the Yankees scored 5.1 runs per game to lead the major leagues. In addition, both the mid 1930s & the early 1960s Yankees teams boasted several good fielders, & this of course aided both Gomez & Ford not only in amassing wins, but also in terms of earned run average, limiting hits & so forth.

Had Gomez pitched for the St Louis Browns (46-108 in 1937) or had Ford pitched for the ’61 Kansas City Athletics (61-100), we might remember them quite differently. Could they have produced outstanding seasons on those teams the way Carlton did for the 1972 Phillies? No one can say for sure; my own guess is they would have been good but not excellent. For instance, Baseball Reference assigns Ford a “wins against replacement’ figure of 3.5 for his 1961 season. Meanwhile, Kansas City’s Jim Archer, is assigned a 3.7—marginally higher in value in terms of producing team wins. Yet Archer’s record was 9-15. On the other hand, Gomez is credited with a WAR of 9.0 for 1937—& 9.0 is outstanding. The highest WAR value of any 137 Browns’ pitcher is Jack Knott’s 2.6. Knott’s 1937 record was 8-18. For purposes of example only, say that the Browns had used Gomez rather than Knott—based on WAR (which is admittedly an inexact science), & assuming that all his “wins against replacement” were added to his own won-lost record, we’d calculate that Gomez would have won 14-15 games total that year. Not bad at all for a pitcher on a really poor team, but not in the realm of Carlton’s 1972 season. Carlton’s WAR in 1972 (again, using Baseball Reference) was 11.7, which actually seems low if we take the figure literally. The next highest win total for any Phillies starting pitcher that year was 4 (a tie between Woody Fryman & Bill Champion)!

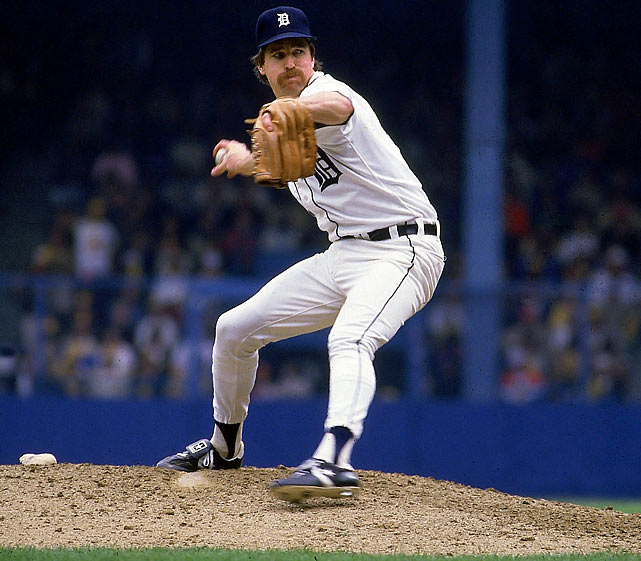

Had Gomez pitched for the St Louis Browns (46-108 in 1937) or had Ford pitched for the ’61 Kansas City Athletics (61-100), we might remember them quite differently. Could they have produced outstanding seasons on those teams the way Carlton did for the 1972 Phillies? No one can say for sure; my own guess is they would have been good but not excellent. For instance, Baseball Reference assigns Ford a “wins against replacement’ figure of 3.5 for his 1961 season. Meanwhile, Kansas City’s Jim Archer, is assigned a 3.7—marginally higher in value in terms of producing team wins. Yet Archer’s record was 9-15. On the other hand, Gomez is credited with a WAR of 9.0 for 1937—& 9.0 is outstanding. The highest WAR value of any 137 Browns’ pitcher is Jack Knott’s 2.6. Knott’s 1937 record was 8-18. For purposes of example only, say that the Browns had used Gomez rather than Knott—based on WAR (which is admittedly an inexact science), & assuming that all his “wins against replacement” were added to his own won-lost record, we’d calculate that Gomez would have won 14-15 games total that year. Not bad at all for a pitcher on a really poor team, but not in the realm of Carlton’s 1972 season. Carlton’s WAR in 1972 (again, using Baseball Reference) was 11.7, which actually seems low if we take the figure literally. The next highest win total for any Phillies starting pitcher that year was 4 (a tie between Woody Fryman & Bill Champion)!The question I believe sabermetricians would ask is this: is a pitcher’s ability to win games specifically a measurable skill? This would address the traditionalists’ concepts of “pitching to the score” (gauging one’s performance to the game score so that one may allow more runs in a high-scoring game & fewer in a low-scoring game) & “knowing how to win.” The traditionalists use such concepts to boost several careers to a stature the sabermetricians believe is not reflected in a deeper understanding of the statistics. Perhaps the most prominent figure in such a debate is Jack Morris, who pitched for the Detroit Tigers & the Toronto Blue Jays in the 1980s thru early 1990s. Not only did he have some high win total seasons, but he also pitched some notable postseason games; as a result, his Hall of Fame candidacy is strongly supported by traditionalists, but decried by sabermetricians, who point to the fact that many of the more sophisticated stats show Morris to be a more-or-less average pitcher on good teams who had a few very good performances in key games.

I remember watching Morris pitch, & I always thought of him as a strong pitcher just based on the games I saw on the television—I never saw him pitch live. As far as him being a Hall of Fame candidate? I defer to the folks on both sides of the argument—Hall of Fame election is so complicated by the inclusion of some players who perhaps ideally wouldn’t be there & the exclusion of some players who ideally should be that it’s difficult for me to take a stand on a player like Morris. I doubt I’d be much chagrined whichever way that plays out. But I do think there’s a lot of force behind the argument that his stats were helped in a significant way by the strength of his teams.

Of course, I always like to complicate these little statistical discussions a bit. While I mostly come down on the sabermetric/contemporary side when considering pitcher wins, I do wonder if their radical devaluation in that community is to some extent a response to the different use of the starting pitcher over the past 25 years. Even thru the 1970s, starting pitchers completed a high percentage of games they started; the prominence of the relief pitcher only began gaining real traction in the 1970s, & the current state of affairs, in which a starting pitcher is presumed to have done his job if he pitches 6 innings allowing 3 or fewer earned runs (a so-called “Quality Start,” tho if he allows the full complement of runs, the pitcher has a decidedly mediocre 4.50 earned run average for the game.) Since the final three innings of the game are frequently in the hands of relief pitchers—& even in a game where the starting pitcher dominates, there’s usually one or two innings handled by relievers—his won-lost record is not only affected by the ability of his team to score runs & play defense, but also by the ability of his team’s bullpen to hold a lead.

For those who aren’t familiar with baseball stats, a “win” is awarded to a starting pitcher who completes at least 5 innings, leaves the game (whether at the end of 5 innings or 9) with his team leading, & with his team never surrendering the lead subsequently until the game’s end. If a relief pitcher loses the lead, the starting pitcher cannot get credit for a win even if his team later comes back to win the game. In fact, some relief pitcher “wins” come in games where this happens & they can be credited with a win despite having pitched poorly! There have been notable examples of this in 2012; the Milwaukee Brewers bullpen has given up leads 26 times when the team had a lead of between 1 to 3 runs (a so called “blown save”); as another example, Phillies pitcher Cliff Lee has a won-lost record of 4-7 despite having pitched almost a full season, having solid stats in other categories & still being considered by many analysts to be one of the top pitchers in the National League. In Lee’s case, the low win total is directly attributable to two factors: a weak bullpen & an offense that has trouble scoring runs.

So here we are again: the chicken or the egg? The pitcher or the team? The answer will say so much about you! As Macrobius said:

You jest about what you suppose to be a triviality, in asking whether the hen came first from an egg or the egg from a hen, but the point should be regarded as one of importance, one worthy of discussion, and careful discussion at that.

All images link to their source

- Steve Carlton: links to http://i.cdn.turner.com

- alimenti,uova,Taccuino Sanitatis, Casanatense, 14th century: Wiki Commons, public domain

- Vernon "Lefty" Gomez, 1933 Goudey Baseball Card: WikiCommons, public domain (copyright expired, not renewed)

- Plutarch, 16th century woodcut: Wiki Commons, public domain

- Jack Morris: links to nationalarmsrace.com

- Francisco Rodriguez, one of the Brewers' main relief pitchers: Wiki Commons; by wackybadger on Flickr (Original version) & UCinternational (Crop); published under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

- Macrobius presenting his work to his son Eustachius (or maybe handing him a baseball card!), ca. 1100: Wiki Commons, public domain

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated, so please play nice!