Hubris: a blind arrogance that unleashes violence, which in turn reflects back on the hero who suffers from hubris, causing his downfall. We know this as the keystone of Classical tragedy: Oedipus, Agamemnon, Creon, all heroic, all destroyed by hubris.

Hubris: a blind arrogance that unleashes violence, which in turn reflects back on the hero who suffers from hubris, causing his downfall. We know this as the keystone of Classical tragedy: Oedipus, Agamemnon, Creon, all heroic, all destroyed by hubris.But it’s an alien concept to U.S. culture: we glorify in super-sizing, whether in the cinematic blockbuster or in the deification of celebrity—& celebrity at this point includes all of the famous, from movie stars to politicians, from sports heroes to the latest reality TV show phenoms. If we have also sometimes gloried in their downfall, it’s not in a recognition of the tragic, but in a tabloid manner: who has been "voted off the island"—at best slightly more akin to the medieval “O Fortuna, Imperatrix Mundi” than to Aristotle’s catharsis, with its notion of terror cleansing the mind & spirit.Our stories aren’t tragic—but do they have that potential?

Let’s consider the story of the greatest baseball player I ever saw perform, Barry Bonds. Whether you follow baseball or not, you’ve almost certainly heard his name, not only because of his unprecedented assault on some of baseball’s most hallowed statistics (he holds the record for the most home runs in a career as well as the most in a season), but also because of his legal troubles that all center on his alleged use of any number of performance-enhancing drugs; according to the book Game of Shadows by Mark Fainaru-Wada & Lance Williams, Bonds was using as many as 10 illegal substances during the final nine years of his career—nine years that saw his performance escalate from that of “merely” great to superhuman.

I speak from a personal perspective, because I saw Bonds play at Candlestick Park in San Francisco during the “merely great” years—by the time his alleged doping had begun, I’d already moved away from Baghdad by the Bay.

A first memory: 1992, & there were already rumors circulating that this would be the Giants final year in San Francisco, & indeed Giants owner Bob Lurie sold the club to a group in the Tampa/St Petersburg area. But the sale was voted down by the National League & a group spearheaded by Safeway tycoon Peter McGowan bought the Giants & kept them in San Francisco. Joy thru the land! But the joy turned to sheer wonder when the Giants signed Barry Bonds, who was a free agent, to a 6-year contract prior to the 1993 season. Suddenly, the Giants were not only staying in San Francisco, but had the best player in the National League, if not all of major league baseball, in their line-up. Bonds had won the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1990, finished second in ’91, won again in 1992. Bonds would finish the ’92 season with a .3411/.456/.624 line; his on base percentage & slugging percentage led the league, & he also hit 34 home runs, stole 39 bases, & scored a league-leading 109 runs to go with 103 RBIs (yes, the despised stat!) His “wins against replacement” figure for 1992 was a stratospheric 8.9.

|

| Candlestick Park in 1965 (with Willie McCovey playing 1b) - a bit before my time in the Bay Area |

Then it was April 15, a night game at Candlestick Park against the formidable Atlanta Braves, National League champions the two preceding seasons, & I was in attendance. Greg Maddux was the Braves pitcher that evening, & he ranked as one of the best in the League, while the Giants opposed him with Jeff Brantley, who was at best a serviceable fourth or fifth starter. I can still picture Bonds’ first at bat against Maddux—there was a sign in right field in Candlestick Park advertising Charles Schwab (a locally-based firm); Bonds hit that sign like a bull’s-eye for a home run (later, the sign was changed to read “Bonds”—obviously referring to both Barry & Schwab.) For the game Bonds went 3 for 4 (home run, single, double) with 2 runs scored & 5 batted in; the Giants won 6-1, scoring 5 in a mere 4 innings on the great Maddux, while Brantley pitched superbly, only giving up 1 run in 7-2/3 innings. There was electricity in the air.

& it continued thru the season. The Giants, even with the addition of Bonds, had been generally predicted to finish no higher than middle of the pack in the National League West—the Braves, who were in the west in terms of the National League, if not in terms of geography—were favorites, & the Cincinnati Reds also had a strong club. But with a combination of strong pitching & defense, timely hitting throughout the line-up & a truly magical year from Bonds, the Giants actually led the Division thru much of the summer. Sadly, it wasn’t to be: the Braves made one of the great surges ever—it was truly a historic race. The Giants won 102 games, the second best record in all baseball, but the Braves won 103 & won the title.

|

| Tom Glavine, one of the ace pitchers for the '93 Brav |

|

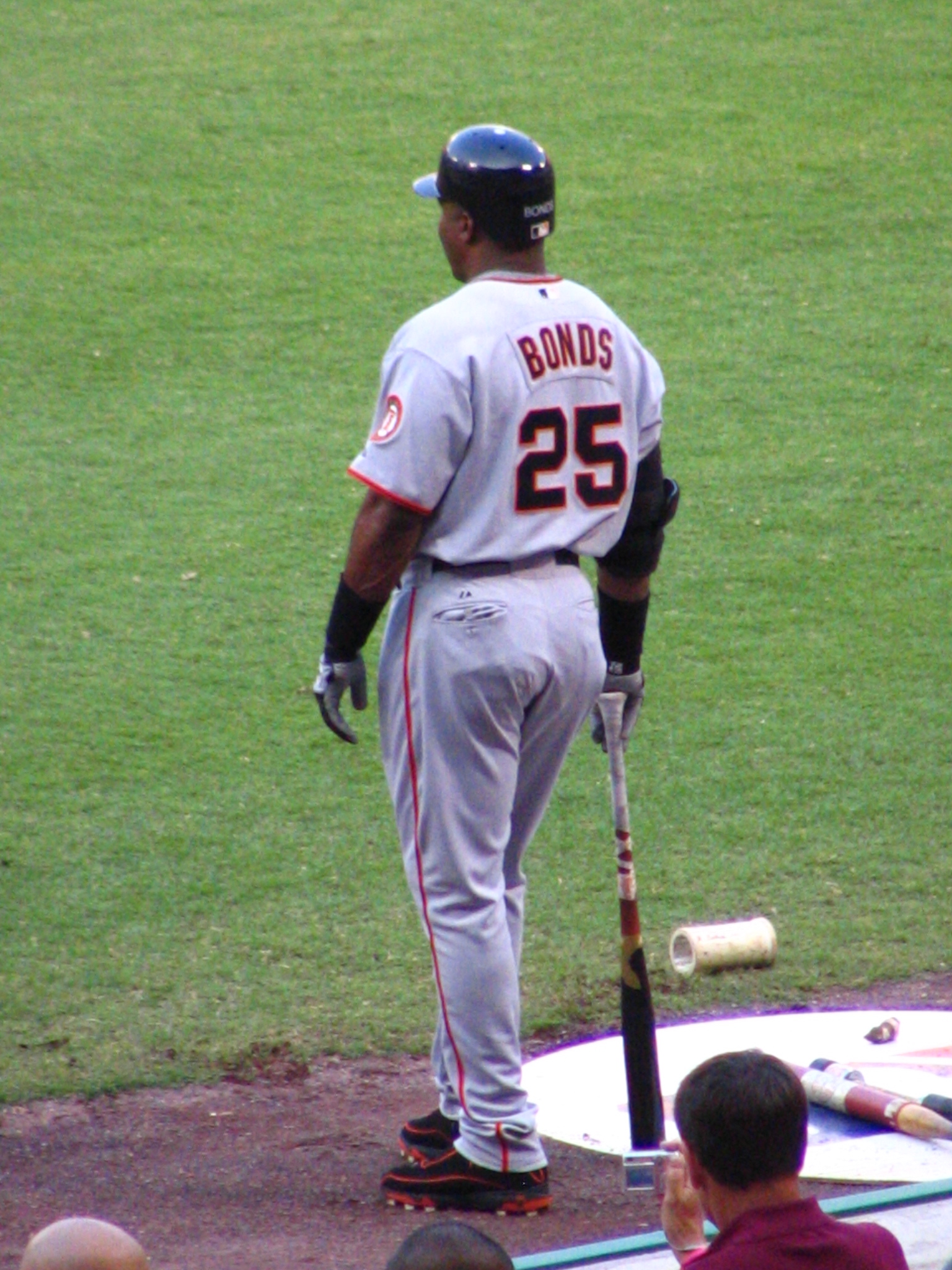

| Bonds transformed: 2006 |

Then in 1999, he showed up at spring training a changed man. As Fainaru-Wada & Williams note in Game of Shadows, the player who’d had the physique of a “muscular marathon runner” now looked like “an NFL linebacker”; his teammates began calling him “the Incredible Hulk,” & joked about “the ‘gamma radiation’ that had transformed him into a muscle-bound superhero.”

From 1999 until the end of his career in 2007, Bonds hit an additional 351 home runs while compiling a .316/.505/.712 slash line, & amassing 1,201 walks: these are video game numbers. In 2001 & 2002, his WAR was 11.6, one of the highest numbers of all time; in 2004 it was a mere 10.4. He broke the single season home run record with 73 in 2001; he led the league in batting average in both 2002 & 2004 with averages of .370 & .362, while hitting 46 & 45 home runs those years. These are superhuman statistics—video game numbers.

Indeed, Bonds had become a video game character: super-sized. Even his head appeared larger, which is symptomatic of using human growth hormone, one of the substances he’s alleged to have used during this time period. As Giants fans, we tried to look away; he led the team to the 2002 World Series against the Los Angeles Angels, & if the team suffered a historic meltdown, losing what would have been a decisive Game 6 after carrying a 5 run lead into the 7th inning, it was not Bonds’ fault. We saw the physical changes, but we tried to believe that they were the product of Herculean workouts as the TV announcers told us. Later, the evidence continued to mount—after the BALCO facility was raided by the feds in 2003, it came out that Bonds’ personal trainer Greg Anderson was charged with supplying anabolic steroids & other illegal performance enhancing substances to athletes, & then in 2007, Bonds was indicted for perjury for his grand jury testimony regarding his involvement with Anderson & BALCO—so then Giants fans took the tack that, sure, maybe he was using, but so was everyone else in the major leagues, so it was a level playing field, even if the entire field was chemically-enhanced. This is still the opinion of many Giants fans when it comes to Bonds.

There is of course, truth to this. It’s widely accepted that the use of these substances was rampant in major league baseball thru the 90s & well into the 00s—I’ll write more about this later—& it’s true that Bonds was far from the only player to undergo a Marvel comics transmogrification.

It’s important to note that the media has always portrayed Bonds as a surly, arrogant man with a chip on his shoulder—in that sense, when combined with his nonpareil baseball efforts, certainly a candidate for the hubristic Greek tragic figure if ever there was one in baseball. I should note that Bonds’ father was Bobby Bonds, an outfielder with the San Francisco Giants (& other teams) in the late 1960s & early 1970s, playing alongside the great Willie Mays during the latter part of his Giants career. Bobby Bonds combined power & speed as did Mays & his son, but he never did reach anything like the level of superstardom those two enjoyed. He was one of the notable “34 true outcome” players, setting a record for strikeouts in 1969 (long since eclipsed), while also leading the National League in runs scored. Because Bobby Bonds developed a friendship with Mays during their time as teammates, Mays was Barry Bonds godfather.

So Barry was baseball royalty: a star player as a father, & one of the top five ballplayers of all time (easily, I would say) as his godfather. It was expected that he would do great things, & he did them—but in the end, attempting to reach unheard of heights, he became a caricature, so much larger than life that he could no longer be believed.

I do think it’s fair to say that Bonds has been singled out as the greatest villain of the steroid era; the reasons for this are complex—baseball as an institution, including fans & writers, are very protective of the single season & career home run records, & there is a sense that these have been sullied. There’s quite a bit of speculation that Bonds was blackballed by baseball when his final contract with the Giants ended at the close of the 2007 season—although Bonds was a free agent, available to any team who wished to bid for his services, none pursued him; & this despite putting up a .276/.480/.565 line in 2007 with 28 home runs (the on-base percentage led the league.) Had Bonds played another couple of years, he would have amassed even further records: he was within reach of 3,000 hits, 2,000 RBIs, & had a good chance to finish with 800 home runs (unprecedented) as well as the most runs scored ever & the most extra base hits. After receiving no offers for two years, Bonds finally officially retired after the 2009 season.

In addition, it must be noted that Bonds, who is African-American, has probably been given less the benefit of the doubt than other players for whom strong circumstantial evidence of drug use exists. Even pitcher Roger Clemens, whose name is often linked with Bonds’ as the other mega-star implicated in the scandal who has also denied the charges, has enjoyed some amount of rehabilitation of late & is even said to be considering a comeback at the age of 50—but then, Clemens like Bonds was never short on arrogance & even hubris.

Is Bonds’ story cathartic? Does it set an example for us about the costs of arrogance? Does it cleanse us in any way? What did he lose? The chance at some further records, certainly, tho it could be argued that those records were never really his to attain; a large shadow cast over what would have been a truly great career without the apparent doping; the real possibility that he’ll be denied entry into the Hall of Fame, despite the fact that even in the years before his alleged doping, his statistics merited his inclusion. Yet Bonds still enjoys massive wealth & popularity at least in the Bay Area; there is even some talk that he may return to the Giants in a consulting position of sorts, possibly even as a hitting instructor. Of course, these latter considerations are facts, & not necessarily truth.

We are a nation that lives by the slogan “We’re #1,” & in general, our culture teaches us to “look out for #1.” The U.S. is big, geographically, & enormous in the psyches of its inhabitants—the children of a Superpower disregard the tragic, equating it with the “sad,” with which it shares little common ground. The tragedy of an Agamemnon or an Oedipus is rife with terror—not the terror of our horror movies, which is a mere frisson in comparison to true existential terror. Can we learn the terror of hubris, the blind arrogance of gigantism from a sports star? We could, perhaps—but we will not. & this is our cultural failure, not that of our tragic heroes.

All images link to their source; all are from Wikipedia/Wiki Commons

- Barry Bonds in 1993: author is Jim Accordino at http://www.flickr.com/photos/jimmyack205/ who publishes it under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

- The "Mask of Agamemnon": photo by Wiki user Rosemania at http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosemania/5705122218/, published under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

- Candlestick Park 1965: by Wiki user Dave Glass; published on Wiki commons under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

- Tom Glavine in 1993: by jimmyack205, published under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

- Barry Bonds in the on deck circle: by Flickr user randomduck, published under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

- A bronze tragic mask, on display in the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus (Athens). It dates from the mid-4th century and is given to sculptor Silanion. Picture by Giovanni Dall'Orto, November 14 2009. The copyright holder of this file allows anyone to use it for any purpose, provided that the copyright holder is properly attributed. Redistribution, derivative work, commercial use, and all other use is permitted.

- Roger Clemens by User Keith Allison on Flickr; published under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

- Theatre mask, dating from the 4th/3rd century BC. On display in the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, housed in the Stoa of Attalus. Picture by Giovanni Dall'Orto, November 9 2009. The copyright holder of this file allows anyone to use it for any purpose, provided that the copyright holder is properly attributed. Redistribution, derivative work, commercial use, and all other use is permitted.

- Louis Bouwmeester as Oedipus in a Dutch production of Oedipus the King c. 1896. In the public domain.

- Barry Bonds in action (2006) by Kevin Rushforth, published under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Hi Kat: Why thank you so much! I do put quite a bit into the posts here, but since I only post about once a week, I feel like I can do that. I know the posts are long, but while I do edit them down some, I give myself permission to write more extensively.

ReplyDeleteI think Bonds & Armstrong are very comparable: both elite sportsmen who have overwhelming circumstantial evidence of doping against them, despite their own denials of involvement. I suppose Bonds is somewhat different in that a significant portion of his career is considered to have been played "clean," while all of Armstrong's Tour de France record is considered to have been accomplished while doping. It may in fact be true that doping is even more pervasive in biking than in baseball, in which case Armstrong may believe he was playing on a level field--I've always suspected that was his thinking. It's a complicated issue, & baseball institutionally also turned a blind eye to it thru the 1990s & into the early 00s--all the extra home runs were good for attendance.

Thanks again!