Do you know the 17th Century Scottish ballad “Thomas the Rhymer”? It’s one of my favorites & has been for many, many years. There are a number of striking moments in the ballad, but one section I’ve long pondered is the following:

'O see ye not yon narrow road,

So thick beset wi' thorns and briers?

That is the Path of Righteousness,

Though after it but few inquires.

'And see ye not yon braid, braid road,

That lies across the lily leven?

That is the Path of Wickedness,

Though some call it the Road to Heaven.

'And see ye not yon bonny road

That winds about the fernie brae?

That is the Road to fair Elfland,

Where thou and I this night maun gae.

Rather than reading this as a sentimental fairy story, “Thomas the Rhymer” has always seemed to me to describe poetic consciousness & the “third way”—a way that navigates between the extremes of straitened & undisciplined thinking; a different focus—indeed, perhaps a radical one.

|

| 1970 Roberto Clemente baseball card: a treasured possession! |

But how does this Child Ballad relate to baseball? Let's take the long way home on this question; I think True Thomas would have approved.

As I’ve discussed in previous posts, the grand world of baseball statistics has undergone a revolution in the past 25 to 30 years. Baseball has always been a game of statistics par excellence, in some ways an inheritance from its cousin, cricket. Traditionally, statistics were pretty straightforward: the major statistics for hitters were batting average (number of hits divided by official at bats); home runs, runs batted in & runs. There were other counting categories, but these were the big four you’d always find on the baseball card. For pitchers, you had the won-lost record, earned run average ((Earned Runs/Innings Pitched) x 9) & strikeouts. By the late 1970s, you’d start to see to see the saves category for relievers. Again, these were the baseball card stats.

|

| As the sign says... |

Since I’ve rehearsed the story of Bill James & the sabermetric revolution in the past, I won’t go into it again here. Suffice it to say that, spearheaded by Bill James’ efforts, a whole set of new & more complex statistics have come into existence, & while some of the most hidebound traditionalists would disagree with this statement, I believe there’s a growing consensus among baseball followers—fans, writers, bloggers, & professional team management—that these new statistics deepen our understanding of player performance, & enable generally more accurate evaluation & comparison.

Of course, a revolution always brings casualties. The old baseball card stats have been devalued to greater or lesser degrees, with the two that have suffered the most precipitous falls being pitcher wins & hitter RBIs.

|

| Prise de la Bastille! |

Now it seems to me that reasonably astute fans have realized for some time that pitcher wins depended on a number of things beyond the pitcher’s personal control; in short, a pitcher on a team with a strong offense & defense is going to win more games than one whose team struggles either offensively or defensively, or both. This is self-evident, tho I probably will write more on the topic in a future post, because I also believe there are some historical considerations at play here.

RBIs are downplayed as well for somewhat related reasons: if a hitter is on a good hitting team & hits at a spot in the batting order that is likely to come around with runners on base, he is more likely to drive in these runners—all other things being equal—than a hitter on a team with a weaker overall offense. Again, this seems reasonably self-evident. One problem that sabermetrically-minded baseball followers have with the statistic is that they believe—rightly I think—that the more traditionally minded baseball followers place an inordinately high value on RBIs, in fact looking at the stat as one of the most important. This is particularly relevant in that many of the traditionalists still hold sway in the Baseball Writers Association, which votes on post-season awards like Most Valuable Player, as well as on Hall of Fame selections.

|

| The Plaques of the five original Hall of Fame inductees |

|

| Miguel Cabrera, with bat |

I’m not here to argue Cabrera’s case either pro or con as MVP—Angels outfielder Mike Trout at a mere 20 years of age is having a season for the ages, & assuming there’s no marked drop off in his performance over the last six weeks of the season, he really would appear to be the logical candidate. But as much as I agree that RBIs are a flawed statistic & that holding them up as some sort of sign of hitterly righteousness is misguided, so too, I’d argue, is a statement that they “mean nothing”—or that (as I heard a well-known baseball personality intone on a national podcast) that if you put anyone at a certain spot in the order they’ll come close to matching that performance.

|

| Julia Kristeva à Paris |

This, to my mind, is the one problem with the sabermetric community: while they’re to be applauded for promulgating statistics that enhance our understanding of the game, its members are not in many cases self-critical. Sabermetrics is in essence a critical method—critical in the sense of a system of thinking designed to understand an art form—whether that’s New Criticism or Structuralism or Deconstruction, etc. At their acme, criticism itself becomes an art form: think Bachelard or Derrida, or Empson or Kristeva. While sabermetrics doesn’t aspire to quite those same “heights,” it can be argued that Bill James’ own criticism thru statistics achieves a sophisticated methodology that brings rewards in & of itself. As a side note on this, it should be noted that James himself wrote, “I advocate, instead, what I call the democratic use of baseball statistics: Let them all speak.” This, to my mind, is Thomas the Rhymer’s “third road;” the quote, by the way, comes from his Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame: Baseball, Cooperstown, & The Politics of Glory.

But let’s look at concrete examples to consider the assertion that “RBIs are meaningless” & the strongly implied idea that any other player could approximate an RBI total by being placed at the same spot in a line-up. Cabrera bats third for the Tigers—the third spot in the batting order is traditionally given to the team’s best all-around hitter. He’s batting behind two players who should be able to get on base a good percentage of the time, & since he should be able to bat for both average & power, he should be able to move those players a good percentage of the time, in addition to being on base himself for the fourth & fifth place hitters, who traditionally hit with power.

So let’s re-arrange the Detroit Tigers batting order, & let’s take Miguel Cabrera out of the third slot—he could bat fourth, certainly. & let’s place in the third slot Brennan Boesch, the Tigers right fielder; after all, right field is traditionally a power position. & let’s compare Cabrera & Boesch using wOBA or “Weighted Batting Average,” a sophisticated sabermetric statistic for understanding offensive performance since it accounts for the players ability to get hits, to reach base in other ways & also to hit for power; it also won’t be skewed in Cabrera’s favor by including RBIs in any way & this creating a circular argument. Boesch’s wOBA for 2012 is .290; Cabrera’s is .412. FanGraphs considers a .290 wOBA to be “awful,” while a wOBA over .400 is “excellent.” While the evaluative terms may leave a bit to be desired, we get the picture; & given that, it seems unlikely that, even with the Austin Jackson getting on base ahead of him at a 40% clip, Boesch’s current total of 48 RBIs would even approach the neighborhood of Cabrera’s 104. Would they increase somewhat—probably. Would they increase at a rate to render Cabrera’s achievement “meaningless?” Doubtful.

|

| Prince Fielder on base |

Let’s try it with a couple of other Detroit players, first their designated hitter & sometime left fielder Delmon Young; Young’s wOBA this year is .300—“poor” by FanGraphs' guidelines. Do his 49 RBI suddenly become 80-90 if he bats third. I wouldn’t bet on it. But to be fair, let’s look at Prince Fielder, the Tigers excellent hitting first baseman; he bats fourth behind Cabrera. Because Cabrera has a high RBI total, you’d expect that to impact Fielder. Prince Fielder’s current slash line is .311/.404/.521, & he has 22 home runs & 88 RBIs. His wOBA is .388—in FanGraphs' terms somewhere between “Great” & “Excellent”—one wonders about the distinction between those words, but we'll let that pass. Could the argument be made that if Fielder & Cabrera were flip-flopped in the line-up their RBI totals also might flip flop as well? Absolutely. Does this have an impact on considering Cabrera as an MVP? Yes, I’d say it gives a good context. Does it mean that RBIs are "meaningless"? I leave you to be the judge.

I love the sabermetric stats & underlying methodology for the deepening understanding of a beautiful & complex sport—an art form. But I’d love to see the sabermetric community follow that third road of Thomas the Rhymer much more often; the discourse about sports could stand considerable toning down on the levels of vitriol, condescension & what we now call “snark.” Let’s consider approaching this poetic game with poetic consciousness!

|

| Thomas the Rhymer - 19th century illustration by Kate Greenway |

All pix link to their source except for the photo of the Clemente baseball card, which is my own.

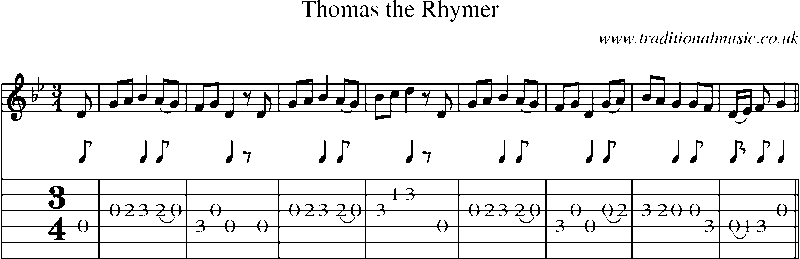

Opening measures of Thomas the Rhymer from traditionalmusic.co.uk

Topps 1970 Clemente baseball card

Bill James 2010 by Wiki/Flickr users Colette Morton and Dan Holden, who publish it under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license

"Prise de la Bastille" ("Storming of the Bastille"), anonymous, unknown date (presumably late 18th/early 19th century), from Wiki Commons; public domain; original located at the Museum of the History of France

Image of plaques of the first five baseball hall of fame inductees (Cobb, Johnson, Matthewson, Ruth, Wagner) by Wiki user Beyond My Ken. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Miguel Cabrera 2011; photo by Wiki user Cbl62 [note: no user page has been created]; this file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Julia Kristeva à Paris en 2008: from WikiCommons. The author, who is anonymous, has released the image into the public domain worldwide.

Prince Fielder, July 13th 2012 by Wiki/Flickr user Keith Allison. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Kate Greenway illustration of Thomas the Rhymer. Greenway was a noted 19th century illustrator of children's books. I was a bit surprised to find how sentimental all the available online images of Thomas the Rhymer seem to be; perhaps my reading of the ballad is in the minority!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated, so please play nice!