“I have read now and then that I am one of the most tragic figures in baseball. Well, maybe that's the way some people look at it, but I don't quite see it that way myself.”

Shoeless Joe Jackson (r), Ty Cobb (l) c. 1913

“Shoeless” Joe Jackson: from WikiQuote, & ultimately from Sport Magazine, 1949

"Jackson's fall from grace is one of the real tragedies of baseball. I always thought he was more sinned against than sinning."

Connie Mack, also from WikiQuote

Major league baseball—Arthurian Legend—the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown—T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland—organized crime—& of course, Bernard Malamud: these are some of the elements of a rare & strange tale!

If you know baseball history, you know that the 1919 Chicago White Sox—later nicknamed “the Black Sox”—threw the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Chicago went into the Series as heavy favorites—the White Sox had won in 1917, & although they’d posted a losing record in 1918, that was directly attributable to their losing some star players to the service in World War I. In ’19, those players—including the great Joe Jackson—were back with the club, & the White Sox fielded a strong line-up that also included future Hall of Fame second baseman Eddie Collins & such hitting stars as right fielder Nemo Leibold & first baseman Chick Gandil. In addition, the White Sox had two of the best pitchers in Eddie Cicotte & Lefty Williams. Cicotte threw his “shine ball,” essentially what we call a knuckleball today, tho I understand that Cicotte actually used his knuckles to grip the ball rather than the fingertips, as in the current usage. In fact, the White Sox had star players at pretty much every position, as well as a couple of fearsome hitters on the bench.

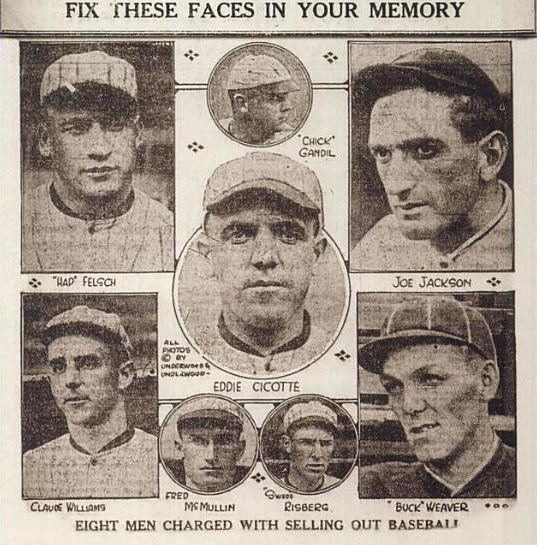

I won’t re-tell the Black Sox story here, tho it is a fascinating tale. If you don’t know about it, Eliot Asinof’s Eight Men Out is a well-known tho controversial examination of the story, but actually the Wikipedia page about the 1919 scandal is a good overview. Briefly, Asinof’s book got its title from the fact that eight members of the Chicago team were implicated: Jackson, Gandil, Cicotte, Williams (not Collins or Leibold), as well as center fielder Happy Felsch, third baseman Buck Weaver, shortstop Swede Risberg, as well as utility man Fred McMullin, who apparently only got in by accident, finding out about the plot & demanding to be included or else blow the whistle on the whole scheme. Although this was never proven, it was alleged that the plot originated with mob kingpin Arnold Rothstein—in The Godfather saga, character Hyman Roth claims to have been inspired by Rothstein, “who fixed the 1919 World Series."

|

| Arnold Rothstein |

Two of the eight claimed they actually weren’t part of the fix: Joe Jackson & Weaver. While Jackson admitted at least initially that he took money, he claimed that he did nothing to contribute to losses, & in fact there are a statistics that give this argument weight: he batted .375 & compiled 12 hits during the Series’ eight games, & he also was credited with no fielding errors & threw a man out at home from his right field position. The 1919 Series was a best 5 of 9 format, unlike the best 4 of 7 that’s in use now (& for quite some time.) Weaver, meanwhile claimed never to have taken any money at all, but he did admit to knowing that the plot was in place.

|

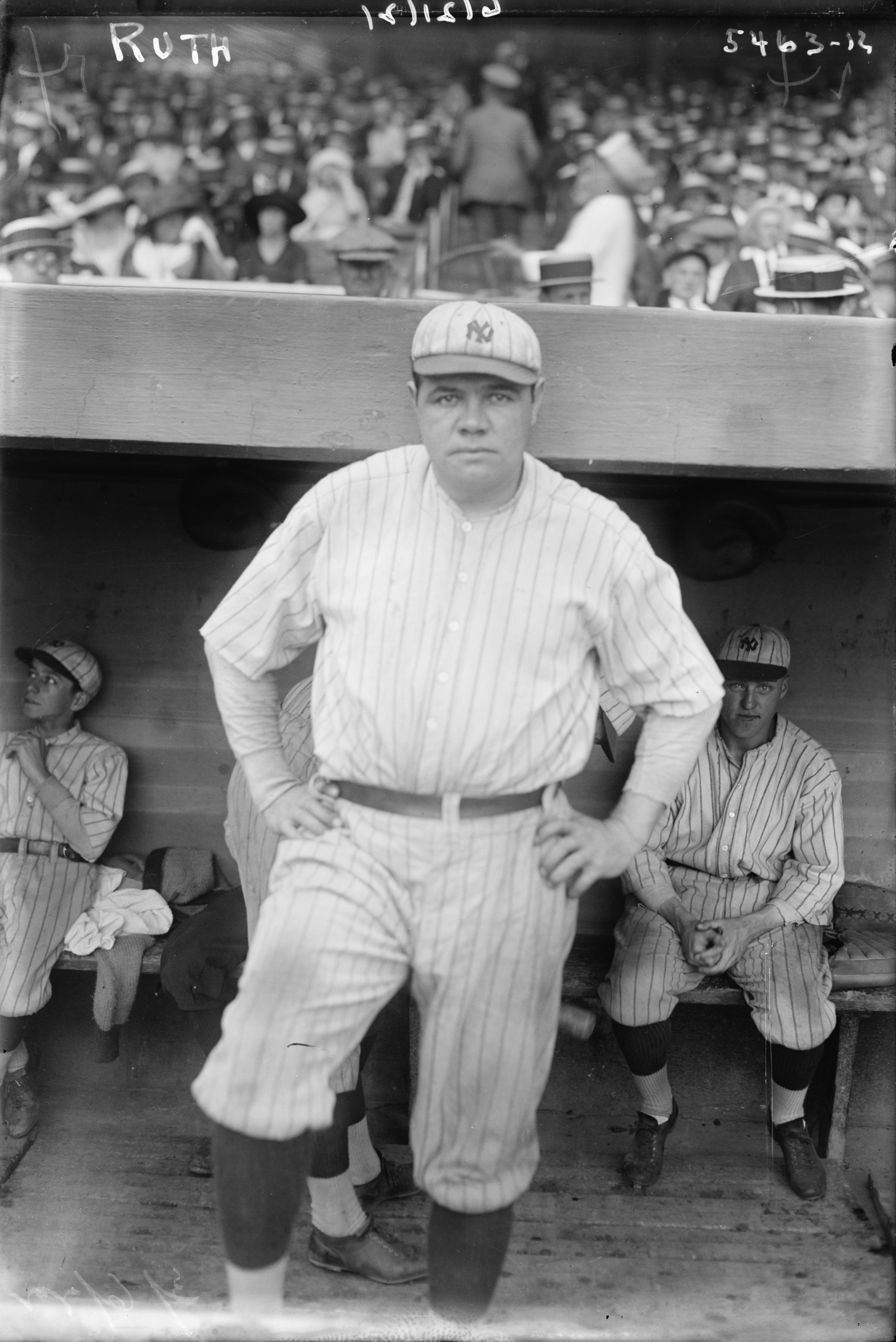

| Babe Ruth, 1921 |

Obviously—at least to baseball fans among you—these are Hall of Fame caliber statistics, & Jackson was consistently among the best hitters of his generation. Testimony from three contemporary Hall of Fame players:

Joe Jackson hit the ball harder than any man ever to play baseball.

Ty Cobb

He was the greatest natural hitter who ever lived.

Tris Speaker

I copied Jackson's style because I thought he was the greatest hitter I had ever seen, the greatest natural hitter I ever saw. He's the guy who made me a hitter.

Babe Ruth

But there’s no plaque in the Cooperstown Hall of Fame for Jackson because following the scandal, Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis declared all eight players to be on the ineligible list, & he remains there to this day.

|

| Judge Landis (c) signs agreement to become Commissioner, 1920 |

If you’ve heard the saying, “Say it ain’t so, Joe,” that refers to Joe Jackson. According to Charley Owens of the Chicago Daily News, a young boy approached him as he left the courtroom & said, “Say it ain’t so, Joe.” Actually, the original was: "One urchin stepped up to the outfielder, and, grabbing his coat sleeve, said: 'It ain't true, is it, Joe?' 'Yes, kid, I'm afraid it is,' Jackson replied.”

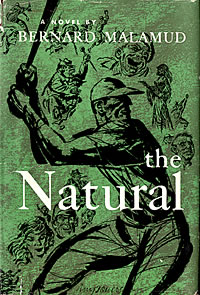

Of course you remember the great ending of Bernard Malamud’s Great American Novel, The Natural:

Roy handed the paper back to the kid.

“Say it ain’t true, Roy.”

When Roy looked into the boy’s eyes he wanted to say it wasn’t but couldn’t, and he lifted his hands to his face and wept many bitter tears.

Roy Hobbs—not Robert Redford triumphing over the forces of evil in the mangled & mendacious film version—more like Robert Ryan, the tormented & magnetic film noir anti-hero. Roy, like Joe, is a “Natural”—not just a natural baseball player, but a “natural man” in the old sense of the word—a simpleton of sorts, in the great tradition of Sir Percival, the questing knight who, in Arthurian Legend, fails to heal the Fisher King during his Grail quest because he fails to ask a question. Critics have drawn close parallels between the Perceval/Fisher King story & Malamud’s novel—of course, that story was very much “in the air” in the first half of the 20th century due to Eliot’s use of it in The Wasteland. After all, one of the main relationships in The Natural is between Hobbs & Pop Fisher. & there are many who claim that Jackson’s country ways & apparent illiteracy were factors in his involvement in the scandal—that he too, in a sense was a “natural man” beyond being a “natural hitter.”

| T.S. Eliot, 1923 - A Red Sox fan |

The failed questing knight: “On Margate Sands./I can connect/Nothing with nothing./The broken fingernails of dirty hands.” Joe Jackson: broken perhaps. But how would he have “cured” the Fisher King or rendered a Wasteland verdant? Indeed, it was in the aftermath of the Black Sox scandal that baseball could have become a Waste Land—until the triumphant home runs of Babe Ruth led us away from the post war bleakness into the impossible 1920s—impossible culture hero, impossible home runs, impossible economy. Baseball always looks to the home run to save it from scandal—look at the late 1990s & early 2000s when baseball tried to obliterate the bitter scandal of the 1994 World Series shutdown; & in doing so, it would seem, struck a new Faustian bargain, as it turned a blind eye to rampant use of “performance-enhancing drugs” until it saw its most hallowed records fall; & then turned against at least the most famous of the perpetrators, both those who were “alleged” & those who admitted to the use of various anabolic steroids & hormonal treatments. More on this at another time.

Joe Jackson, in the longer version of the quote that begins the post, said he’d accomplished all he wanted to in baseball, & so the ban didn’t matter to him. He was 32 years old in 1920, his last season prior to being declared ineligible, so it is likely that Jackson was past his peak—tho he did put up a .382/.444/.589 slash line, & also record a league leading 20 triples & a career high 12 home runs that year. But that’s Jackson the man not Shoeless Joe the legend. Not the legend who morphs into Roy Hobbs, embodiment of American grandiosity & eventual fall not only from innocence, but clear into damnation—the most American of damnations: the star baseball player whose records are expunged; the celebrity who becomes unknown & indeed unknowable.

The stuff of deep legends—on the superficial level of the film Field of Dreams, or on a deeper level where the exaltation & subsequent debsement of those we hold up to the iconic light of celebrity becomes a national fixation; or on an even deeper level yet where the exploits & foibles of these celebrities & sports stars somehow intertwine with deep myths. Shoeless Joe Jackson was among the first of these in our ongoing myth cycle; he is not the last, not even from the myth cycle of baseball.

Everything he hit was really blessed. He could break bones with his shots. Blindfold me and I could still tell you when Joe hit the ball. It had a special crack.

Wiki Quote: Ernie Shore, as quoted in Baseball America (2001) by Donald Honig, p. 107

All images link to their source on Wiki Commons/Wikipedia. All images are in the public domain except the cover image of The Natural, for which Wikipedia claims fair use.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated, so please play nice!